Molecular Coevolution

The structure and function of macromolecules result from the interactions of their constitutive parts. These shared constraints lead to genetic interactions called epistasis [1]

: the fitness effect of a mutation at one position in the genome varies depending on the sequence states at other interacting positions, possibly in the same gene, or in another gene of the same genome, or even in the genome of another species. From an evolutionary perspective, this means that these positions will not evolve independently. This non-independent evolution of genome positions is what we call molecular coevolution [2]

.

The detection of coevolving positions from sequence alignments has a rather long history, which we can trace back to the first sequences of tRNA obtained in the 60s: comparing the set of possible Watson-Crick base pairing configurations in a few tRNA sequences enabled the establishment of the clover-leaf structure model. Comparative sequence analysis of sequences has since then been successfully employed to infer secondary structures of other RNA molecules. Extension to proteins came later, offering significant additional challenges. The size of the alphabet (20 amino-acids instead of 4 nucleotides, sharing various partially redundant biochemical-properties), and the multiplicity of possible interactions prevent simple approaches from detecting enough biologically relevant coevolving candidates. More elaborate statistical approaches, however, including machine learning algorithms, have proved to be able to extract structural signal from sequences alone, culminating with the recent success of AI algorithms in predicting protein structure from sequence information alone.

That sequences covariation contains information about protein structure is now widely accepted, and proved to be of emprirical importance. That epistatic interactions, and in particular, compensatory mutations, can lead to coevolution was also theoretically shown. It was also reported that sequence covariation patterns are generally good predictors of epistatic effects. Yet, much remain to be understood about the link between structural constraints, epistatic interactions, and coevolution. Notably, how much compensatory mutations, which are predicted to be rare, occur in protein evolution? How much do they contribute, as a causal mechanism, to the observed patterns of sequence covariation?

Detecting coevolving positions from sequence data

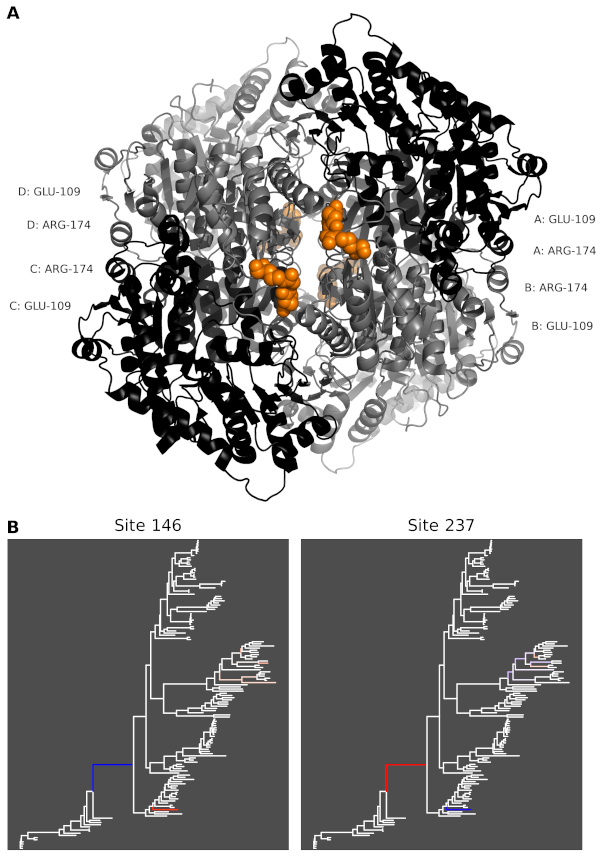

To detect coevolving positions, we first map all substitutions, for every positions in the sequence alignment and every branches of the underlying phylogeny, via a procedure called substitution mapping [3] (Figure 1)

. The underlying algorithm makes use of a model of sequence evolution, to properly account for possible multiple substitutions on a branch, variation of evolutionary rates between sites, and the uncertainty in ancestral states at the inner nodes of the phylogenetic tree.

The resulting substitution maps serves as input to several measures of coevolution between two or more sites [4]

. We aim at detecting co-substitutions, that is, mutations at two positions that were fixed in the same branches of the phylogeny. The statistical significance of the coevolution statistics are then assessed by simulations, by generating alignments using phylogenetic models of sequence evolution, as inferred first on the real data. The simulated dataset replicate the real data in many aspects, notably the underlying phylogeny and site-specific substitution rates, yet with all positions evolving independently. This allows to estimate the distribution of the coevolution statistics under the null hypothesis of independence. All calculations are implemented in the open-source software (CoMap).

Legend of Figure 1: The studied protein is a homotetramer (A). The two coevolving positions undergo compensatory mutations, at least on two branches of the phylogeny (B). Mutational changes (here for amino-acid charge) are depicted in red (charge increase) and blue (charge decrease). See [5] for details

.

Building an atlas of protein coevolution

We aim at characterising the frequency, type, and ditribution of compensatory mutations in protein evolution. With Dr Shilpi Chaurasia, we built a large dataset of protein families for which at least one 3D structure was available

.

We used the HOGENOM6 database as input, realigned all protein families, filtering sequences and sites to obtain a currated dataset of 1,630 alignments and corresponding protein structures, encompassing species from the bacteria tree of life.

We reconstructed each family's phylogeny and run the CoMap method to detect groups of coevolving positions.

We focused on positions coevolving via compensatory mutations, using biochemical indices as proxies for fitness effects.

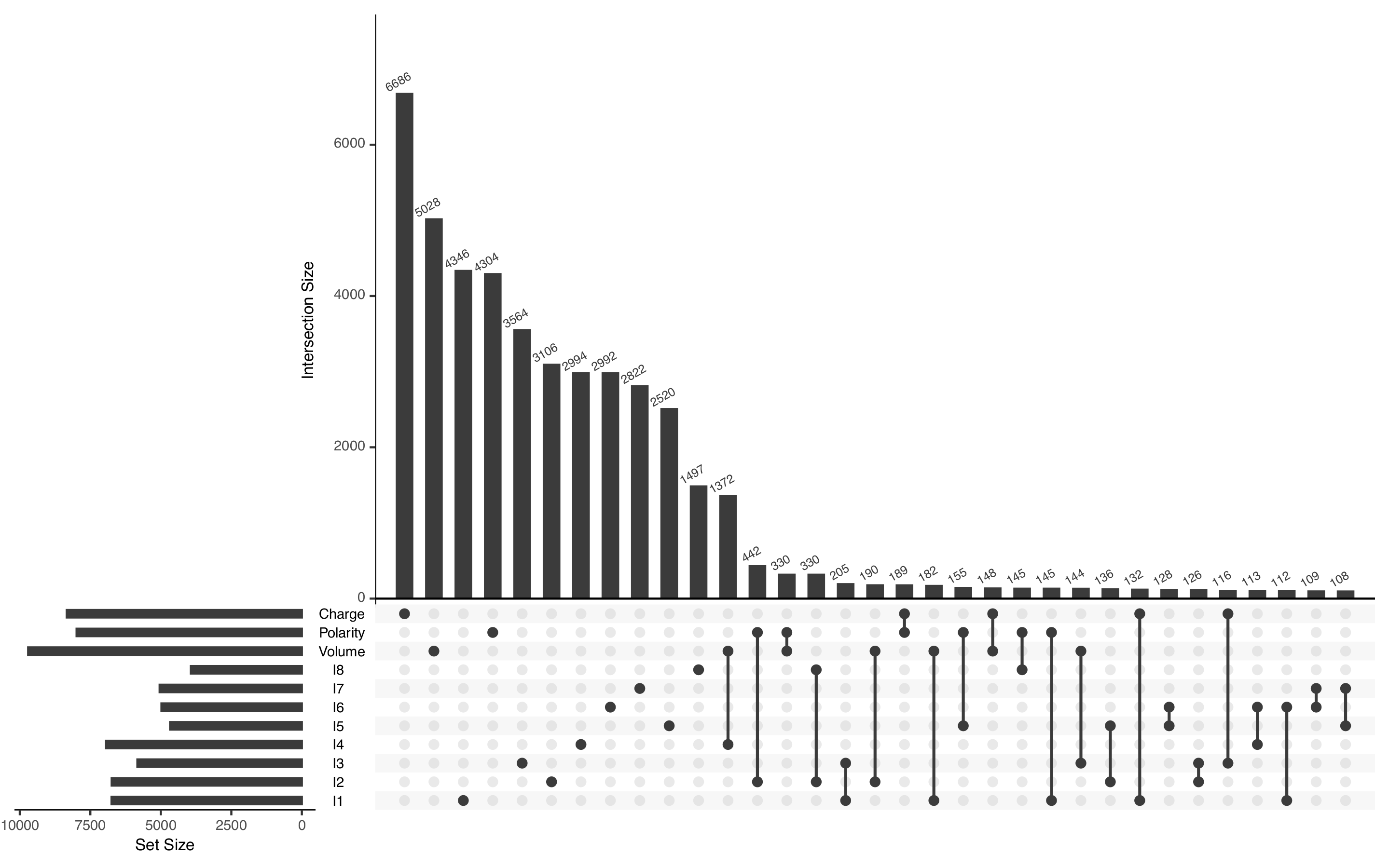

In addition to the classical "volume", "polarity", and "charge" properties, we used 8 genetic indices encompassing a broad range of biochemical properties.

This allowed us to detect 51,661 coevolving positions among 366,794 analyzed positions (Figure 2).

We then used statistical analyses to establish the properties of these positions.

Our results show that coevolving residues tend to evolve slowly. They are also more often located at the core of proteins, far from the surface, and outside secondary structure motifs, but tend to be in contact in the 3D structure. These results hold after accounted for various possible confounding factors. Interestingly, sites coevolving for charge compensation have a distinct pattern: they evolve faster and are exposed at the surface of proteins.

Our results show that compensatory mutations are rare, but widespread among proteins. They also highlight the existence of an intermediate level of selective pressure in protein structures, where inter-residues interactions enable protein structure and functions.

Legend of Figure 2: UpSet representation of detected coevolving positions. The majority of positions are uniquely found by one method, and the "classical" biochemical properties "volume", "polarity" and "charge" lead to the largest number of coevolving positions.

Experimentally assessing epistatic interactions

As part of his PhD work, Dr Bilal Haider selected candidate positions with a strong signal of coevolution and with inferred cosubstitutions on the E. coli branch to assess whether compensatory mutations are the mechanism behind the inferred cosubstitutions. He then inferred the ancestral sequences in silico using models of sequence evolution, and resurrected the corresponding genotypes by reverting the mutations in E. coli extant strains. He used competition experiments to infer pairwise relative fitness values for each genotype, and fitted models of fitness landscapes to infer the fitness effect of each mutation. Results are reported in a manuscript currently in preparation.

References

- Achaz G, Dutheil JY. Correlated evolution: models and methods. arXiv. . arXiv:2103.11809.

- Galtier N, Dutheil J. Coevolution within and between genes. Genome Dyn. ;3:1-12. doi:10.1159/000107599.

- Dutheil J, Pupko T, Jean-Marie A, Galtier N. A model-based approach for detecting coevolving positions in a molecule. Mol Biol Evol. ;22(9):1919-28. doi:10.1093/molbev/msi183

- Dutheil J, Galtier N. Detecting groups of coevolving positions in a molecule: a clustering approach. BMC Evol Biol. ;7:242. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-242

- Chaurasia S, Dutheil J. The structural determinants of intra-protein compensatory substitutions. biorXiv. . doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.11.11.468231